Saturday, May 30, 2020

Tuesday, May 26, 2020

Wednesday, May 20, 2020

Monday, May 18, 2020

Friday, May 15, 2020

Wednesday, May 06, 2020

Saturday, May 02, 2020

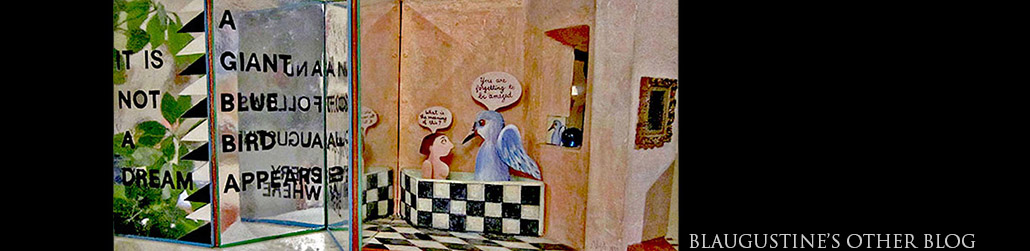

SHOWERING THOUGHTS

I

spend far too long taking a shower but it's my favourite place to

think. The shower is not fancy, it's just an ordinary one over the

bathtub with a striped shower curtain. But it's where my thoughts

crystallize into words and sentences. Maybe the needles of hot water

gently pricking my skin act like some kind of psychological acupuncture?

Or maybe not.

What I'd like is a waterproof recording device that can be attached to the tiled shower wall and remotely connected to my computer so that I can ruminate into it and then see this later on my computer screen as well as printed out on paper.

Now it's almost 5pm...FIVE PM...and I haven't been out to do my shopping yet.

Back soon with another installment of the illustrated memoir.

What I'd like is a waterproof recording device that can be attached to the tiled shower wall and remotely connected to my computer so that I can ruminate into it and then see this later on my computer screen as well as printed out on paper.

Now it's almost 5pm...FIVE PM...and I haven't been out to do my shopping yet.

Back soon with another installment of the illustrated memoir.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)